This essay is based on a work originally published in the Georgetown University Dept. of Religious Studies journal special edition on Buddhism and Film, April, 2017 (ISSN 2077-1444).

Once a film is finished it goes out into the world, forges relationships with strangers, steps into a life of its own. That’s when it is time to turn toward new ideas. A year or so after I finished my film, ONE MIND (2015), I was invited to write an essay on the topic of Buddhism and film. I was already deep into my own rumination on the topic, trying as an artist to formulate my approach to film as a contemplative art - a kind of working theory to guide my work. So this invitation unfolded as an opportunity to consolidate what had only been a pile of ideas, a stack of intuitions and an artistic vision born of my life and practice as a Buddhist.

Many of the films we call “Buddhist” films are films about Buddhism. What I want to talk about here is cinema as a Buddhist art-form. I want to look deeply at cinema itself - the language, grammar and forms of cinema - and find in this a dynamic art-form suited to celebrating, sharing, and exploring the Buddhist contemplative life. Within Buddhist traditions around the world, calligraphy, poetry, painting, iconography and architecture evolved, over centuries, into the Buddhist art forms we know today. These forms have adapted to express the inexpressible; the contemplative’s internal experience. How do we craft cinema that turns us inside out like that, giving shape to what is within us?

I am a Buddhist and a meditator and an artist—a filmmaker. These were once divided and estranged elements of my life. Below, I have pieced together just how and by what process these elements have united for me as an artist, into a working approach to Buddhist contemplative cinema. I also want to talk about why I think all of this is worth doing at all. Why it matters.

On The Road

It was right around the time I was heading into college that I started getting interested in the contemplative life. I began reading a lot then, and Hesse, Salinger, Maugham, and Kerouac were taking me on epic, soulful adventures. Whether they took me to a living room on the Upper East Side, or to a yogi’s hut in India, their writing had an incandescence—glowing from within with inquiry and a spiritual longing. This felt new to me and was the beginning of a profound shift within me. One which illuminated a vast inner world that I was eager to explore.

Looking back, what I found in their writing was a simple shift in perspective toward a wider view of life. One that respects the full spectrum of human experience—what lies between joy and suffering. The messages surrounding me—gleefully encouraging everyone to turn away from the difficult, shadowy side of life—were leaving me empty-handed when it came to the vicissitudes of life. Billboards, television, and checkout-counter magazines said happiness is somewhere out there, in the opposite direction of the darkness. That you find happiness with your back toward sorrow, pain, longing, and disappointment. A whole part of life felt hidden, and yet full of meaning; taboo but honest. I did not want to abandon that darkness. Within me boiled an eagerness to rebel against these great perpetuating myths about happiness.

Right around that time, by a miracle of serendipity and some great advice from my academic advisor at The College of Wooster, I landed in Dr. Ishwar Harris’s intro course on Buddhism. Dr. Harris gave me a seat in his class and literally everything changed for me that day. I heard the Buddha’s life story for the first time, and it was revelatory. The Buddha embodied that rebellion I felt evolving within me. I learned that the Buddha was a prince and that his parents had him cloistered in a palace, hiding him away from the inevitabilities of sickness, old age, and death. But he abandoned palace life and struck out in the night, cutting off the royal locks which were a symbol of his princely rank, he entered into the forest to meditate and live the contemplative life. He turned his gaze inward and committed to a path.

What he left behind for us is the Dharma. Practical and simple, yet evolutive teachings on how to become a kinder and wiser being in this world. I had found my shift in perspective, and with it, a lifetime of creative exploration.

The Contemplative Gaze

Subhuti, if a bodhisattva should thus claim,

‘I shall bring about the transformation of a world,’

such a claim would be untrue. And how so?

The transformation of a world, Subhuti,

the ‘transformation of a world’ is said by the

Tathagata to be no transformation. Thus is it called

the ‘transformation of a world’. (Red Pine 2001, p. 304)

In college I found opportunity to deepen my exploration of Buddhist thought and culture. At the same time, I was getting interested in art. I’d started reading the poems of a Tang Dynasty hermit poet named Cold Mountain. Jack Kerouac affectionately called him a Zen Lunatic (Kerouac 1958) and seemed to identify with his aesthetic sensibility and his rebellious tone, and so did I. Around that time, Bill Porter wrote a book called Road to Heaven (Porter 1993). In it, he said there are hermits like Cold Mountain living in modern China now, just like in the old days. So, after school, off I went on the road to find Cold Mountain myself.

In my documentary, The Mountain Path (2020), you meet the hermit monk whom I still call my teacher today. He taught me how to read scripture, and he taught me how to meditate. He is a true mountain monk with a straightforward but creative sensibility. He taught me how to sit and explore the forms and capacities of my mind in a way that spoke directly to my own idiosyncrasies and sensibilities as an artist and a young person. Every time I hiked down that mountain trail from his hermitage, the world seemed a little different than it did on the way up. And over the many years of meditation practice to follow, in both Chan and Vipassana traditions, a whole new way of seeing and engaging the world started to emerge within me—a way of seeing I will call here the, “contemplative Buddhist gaze.”

Contemplative gaze to me means living with an awareness of mind—just that basic recognition that within us is a great mindscape, and what goes on in there defines what goes on out here, in life and how we experience the world. Once we start paying attention to that, taking up a meditation practice to strengthen it, we step into the contemplative life. But the contemplative gaze is not an enlightened gaze—it is just a shift in perspective that happens naturally when we practice meditation. We may discover ourselves standing anywhere on the spectrum from confused to enlightened, and that does not matter here. What matters is the gaze. With the gaze, you are on the Path. And I think the Path is what Buddhist contemplatives share regardless of where we find ourselves on it.

First, we turn our gaze inward and discover our capacity to pay attention and observe our own body and mind. We work on increasing the fidelity of that attention, the breadth and depth of observation. At first, every thread of our being rebels. It feels awkward and unnatural and even painful. But we learn to stay put, sit still, and stick with it. Slowly, as if a light were turned on, shapes begin to emerge. The forms and structures of the mind and of the self-mechanism gain definition as they emerge from the shadows. Mind becomes something workable, something we can relate to. And we can explore in that space. Like the sun rising over a mountain valley, shadows recede, and there is a lovely stream flowing and some patches of dark forest, a cliffside overlooking a grassy pasture, maybe some creatures are milling about. These are not hallucinations: I am just saying that is what it feels like in there—that living, dynamic richness and topography.

When we stand up and open our eyes, the inner world recedes to the background again. Concentration is broken by the world’s shower of signals, and like from out of a cave into the light of day we go. Over time, though, the contemplative gaze inward becomes so strong and resolute that even as we look outward, we can hold that gaze, unwavering, and carry it out into the world and into our lives. This is a miraculous thing, a blossoming of the contemplative gaze. The inner realm and the outer realm unite into a single, unified field of experience. The world suddenly feels rich with meaning, and whole. As with the explorations of the inner landscapes, insight is inherent in every experience.

Different Buddhist meditation traditions might define this contemplative gaze in different ways. I practiced Chan meditation in China for many years before that pointed me toward Vipassana. I can only speak to my own personal experience and how complimentary both traditions have been in my own life as a Buddhist practitioner and a Buddhist artist. Chan opened me up to the power of inquiry, vulnerability and the nature of mind—its fundamental, spatial qualities. Vipassana turned me toward understanding body, form, structure, and the self-mechanism.

Regardless of the tradition practiced, by what method you cultivate it, for me, this contemplative gaze is a fundamental shift toward what is essentially an artistic perspective—from a life lived for what we see, to a life lived for how we see. It is a shift away from distraction, toward presence. From a reactive relationship with the world toward an illuminating gaze upon the world. This is a definitive contemplative Buddhist experience. We are not talking about states of euphoria or being carried off somewhere. And inherent in this gaze itself is a power to heal and evolve—to move toward buddhahood.

New Art for an Old Path

What does this have to do with filmmaking? When we look at a work of art, we bring our whole being with us in that moment—our karmic baggage body—everything that colors the way we see the world. Art can be like a mirror that reflects back to us who we are in that moment. We see things, but in those things, we see ourselves too; our past, our aggression or our passion relating to that thing, all reflecting back to us. Everything is aglow with this incandescence. And some art calls on us to engage that reflecting itself and deepen it.

There are many things in this world that are crafted to distract us—carry us away in emotional reveries. I do not want to totally dismiss the value of entertainment, but I must point out this important distinction. Contemplative art is not a distraction, it is an illumination. It gives form to the ineffable, takes it out of the shadows, makes it workable, makes it relatable. The art impulse has always been about giving shape to mystery. From the Buddhist perspective, the mystery is mind itself.

Traditional Buddhist art forms such as calligraphy, landscape painting, poetry, and story have given shape to this contemplative experience for many centuries. Years ago, I had a book on the Zen Arts that I cherished deeply. And in it was a big, beautiful black and white photo of the Ryōanji rock garden in Kyoto. A couple years ago, my wife and I went to see that garden. The first glance through the frame of dark timber pillars and roof beams took my breath away. From the viewing-veranda, the precision of the craftsmanship of the whole garden, the angles, the composition, the textures—it is like being in the presence of mind itself. There is a skillful utility of form and means that resonates with the mindscape within us, lights it up, and grounds us in presence and attention. I thought, there has got to be a way to make cinema as elegant and powerful as this.

When I began filmmaking—looking at the world through a camera and exploring the chemistry between image, sound, structure and rhythm—I began to see how the distinctive multidimensional quality of the cinema-viewing experience makes it suitable for celebrating, sharing, and exploring the Buddhist contemplative experience as I know it and as I see others living it. I look for inspiration from cinema masters like Andrei Tarkovsky, Yasujirō Ozu, Werner Herzog, Agnès Varda, Terrence Malick and David Lynch, who each in their own way are wrestling with the formal qualities of cinema itself because they know that’s where it happens - bringing to life the inner world of their characters. They work at such a transcendent depth in their art, working with cinema as a language to express a mysterious and profound inquiry into human experience, that I think their cinema naturally embodies something contemplative. Even if they themselves would not describe it as such. In their work, I recognize the contemplative principles that I want to explore though film as a Buddhist artist.

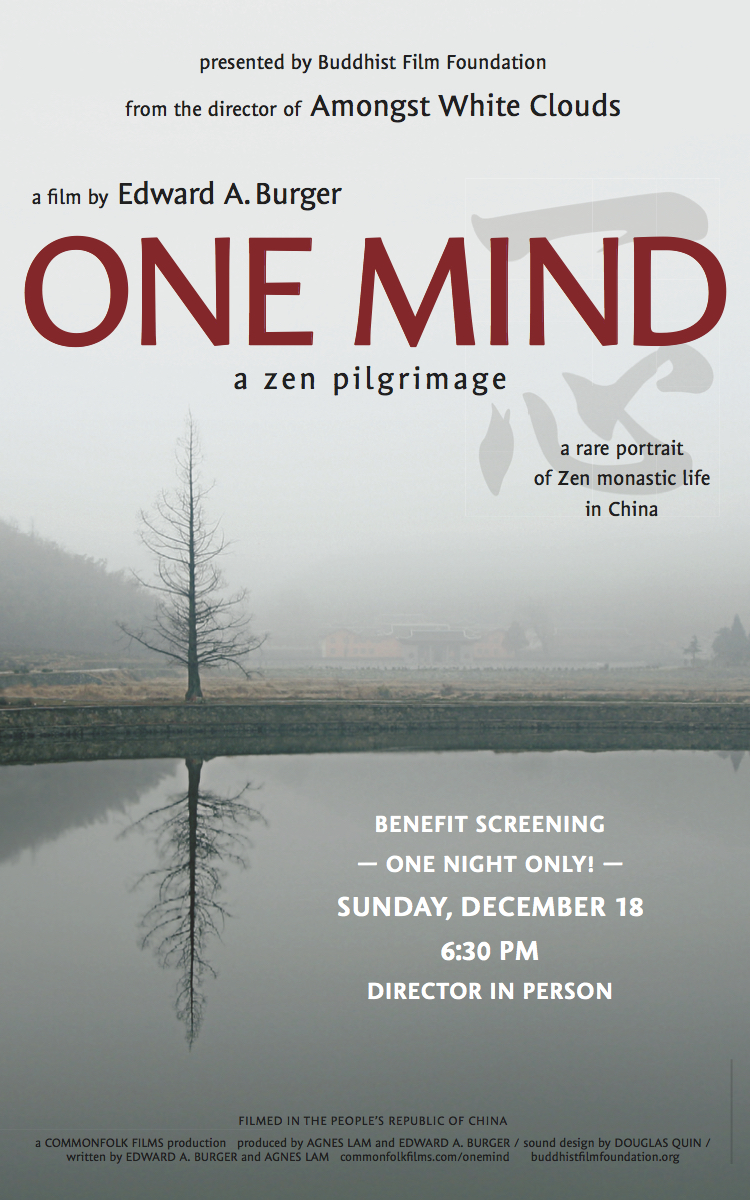

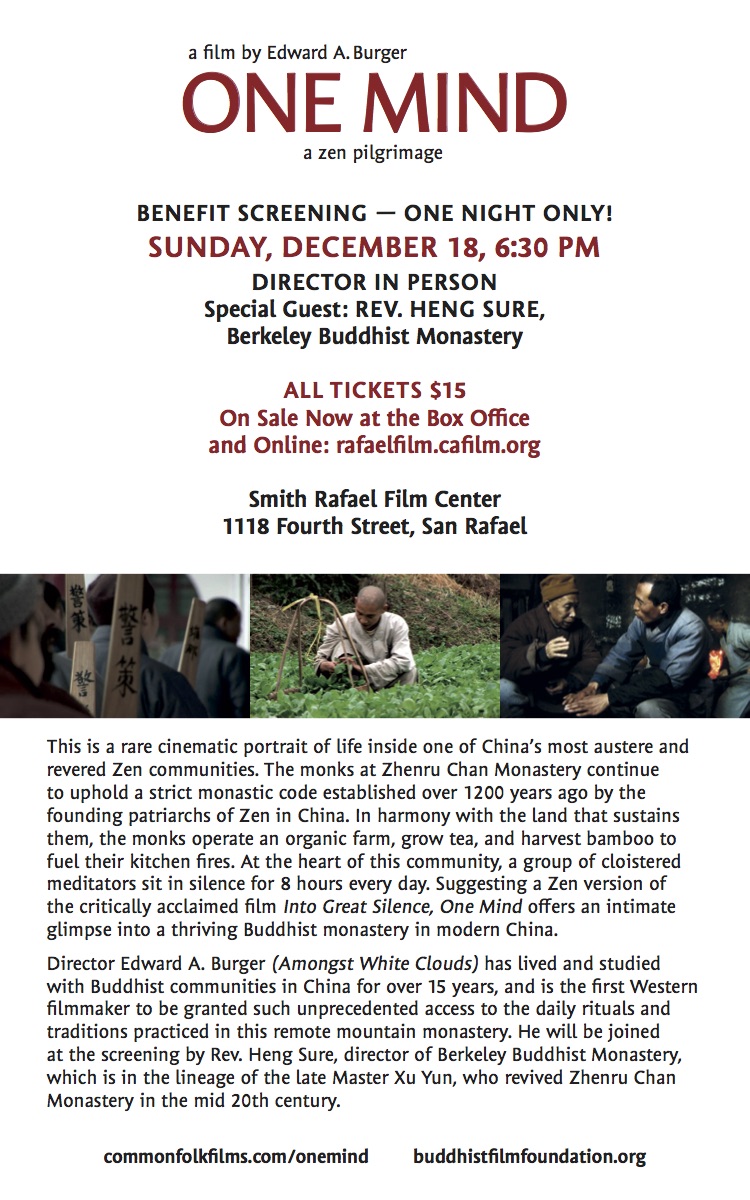

ONE MIND - A Study

ONE MIND began as a simple documentary project. I lived at the monastery. I filmed everything I saw. But I was sitting meditation with the monks five times a day too, and they were teaching me how to live properly within a Chan monastic community. They taught me how to see the monastery as a sacred space, read the architecture, hear the sounds, feel the presence of iconography and listen to the guiding voice embedded in the minutia of the monastic precepts. ONE MIND is an artistic experiment born out of what I learned. My filmmaking approach evolved as my understanding of the dynamics of contemplative life deepened. In post-production, it was sometimes frustrating to work with the earlier footage, which was not imbued with my later, more clarified approach. This showed me how important it is that all dimensions of the filmmaking process cooperate in a well-defined vision that informs each cinema moment. I see in ONE MIND some failures and some successes. It is a study in contemplative Buddhist cinema.

Living Narratives

The first time I visited Zhenru Chan Monastery I fell in love with the place. I had been studying with Buddhists in China for seven years at that point but had not seen anything like this yet. Zhenru is a big working farm run by monks. And the red-brick buildings, the creaky wooden floors, the smell of wood-fire from the kitchen, and beautiful, big gardens felt like home to me. The monks there are meditator monks, and you can tell. Life in the meditation hall lends the Chan monk a very distinctive gait, and life there in the mountains, a certain athleticism. This was a farm community for meditators—and I could hardly believe such a place existed in the world. Naturally I wanted to make a film. It has alway been my way of exploring Buddhist traditions. I set out to make ONE MIND.

Every year at Zhenru, there is a Chanqi winter meditation retreat. Footage from this arduous, wintry lockdown bookends ONE MIND and inspires the entire approach of the film. During the chanqi, the meditation sessions begin with a stirring ritual. One I would find out later is a stylized adaptation of the Sudhana story from Chapter 39 of the Avatamsaka Sutra. But when I stepped into this ritual it felt like pure theatre; like a communal performance meant to celebrate and inspire the contemplative journey before us.

As the meditators circle the meditation hall’s central altar at an ever-quickening pace, four of the senior monks peel away and take a position at one of the corners of the hall. Then, one by one, each raises his xiangban—a ritual implement in the shape of a long wooden sword—high over his head and calls out loud and in a long and drawn-out deep tone:

Qiiiiiiiii!

Still walking briskly but hunched at the waist in a deep bow, together we bellow a unified response:

Qiiiiiiiii!!

This call and response continues until finally, a signal is struck and with heaving chests, we disperse to find our seats on the meditation bench around the periphery of the hall. Meditation begins.

During a break, warming our feet around a brazier of glowing coals, I asked a senior monk the meaning of this ritual, and he told me this story:

A pilgrim named Sudhana went on a journey to find Maitreya, the Buddha of the Future. Maitreya lived in a fortress, and when Sudhana arrived at the fortress he discovered it had no gate to enter by and no windows. Dumbfounded, Sudhana considered how he could enter the fortress. Just then Manjusri, Bodhisattva of Wisdom, appeared beside Sudhana and grabbed him by the robe with one hand and with his sword of wisdom held high in the other hand, shouted “Qi!”—and pulled Sudhana through the wall of the fortress and into its inner chamber. There, the young Sudhana stood, face to face with Maitreya, the Buddha of the Future.

It is a journey like many other epic journeys, and the fundamentals of the story are found in a well-known sutra. But in its telling here (a rendition told by a Chan monk tasked with instructing me in a centuries-old meditation method) we see clearly its distinctly Zen characteristics: a gate-less fortress that calls to mind the “gateless gate”, Sudhana’s charged pause, and Manjusri with his sword of wisdom cutting through the impenetrable with a “sudden” and piercing wisdom. Meeting Maitreya being akin to Bodhidharma’s “seeing one’s mind, realizing one’s [buddha] nature.”

Finally, each meditator takes on the remaining leg of Sudhana’s journey, each within the theatre of their own inner mindscape.

I recognized then that I was participating in a kind of lived storytelling. And I looked around the monastery to discover the entire canon of traditional Zen narratives not only being told and passed down between monks and masters but also being performed with the same visceral dimensionality in the everyday life of the monks there. I felt as if I had woken up from a stupor or tuned in to a secret frequency broadcast. Finally I could see P’u Ming’s Oxherd Pictures come to life in the monk who tends the monastery oxen. Gong’an like “zen and tea are one flavor” come to life in the yearly tea leaf harvest and the quiet deliberateness of ceremonial tea drinking before evening meditation. The “field” of mind and the “thicket” of views all came to life in the bucolic landscape of this farming community. Even the shape of the monks’ bowls speak a narrative. The way they ring a bell or plant a sprout in the garden. All of it part of what you could call the “everyday” of Chan monastic life there.

As a meditator and as an artist, I sank a layer deeper into the rich embrace of that life at Zhenru Chan Monastery and I knew that I could learn something, as a filmmaker, from these lived narratives. I was, after all, looking for a way to make a film about this community that does not just show like a portrait, or explain like a slideshow presentation, but a film that is of that experience itself—a film where form and subject are unified.

The Organic Soundscapes

Picture is how we see space, but sound is how we feel it. R. Murray Schafer writes in his book, Soundscape, “Hearing is a way of touching at a distance and the intimacy of the first sense is fused with sociability”.

Zhenru Chan Monastery is in the mountains and remote. The community is mostly self-sufficient, and that magnifies the contemplative atmosphere of the place—adding a layer of sanctuary to it. Our sound designer, Douglas Quin intuited that, and he crafted an immersive world through music and sound-design to reflect that. His soundscape is of the place and is crafted to serve the film’s inward trajectory. Working with location audio recordings and instrumentation carefully chosen to be in natural harmony with the environment at Zhenru, he created what I call “musical elements” to evoke a sense of mystery in certain scenes, or as cues in the narrative, especially at shifts in perspective. In some passages, Doug used processing and manipulation of location audio recordings, transforming them, as he describes it, “to reveal their inner workings and worlds of sound within sound”. In this way, the ONE MIND soundscape reflects the deepening gaze of meditation, is in tune with the inward journey, and has the feeling of having emerged from within the place itself. Nothing seems to enter from the outside. You step into the world of the monastery and everything you need is there in that space. Like when we sit down to meditate; everything you need is there—breath, body, mind.

If we can slow down and let it, sound can be a rich and visceral adventure. In cinema, sound invites us to look deeply into long, suspended shots—past simple metaphor, and into a sense of environment, where life is being lived in the world of the film. Wind rustles a bush here, a foot steps there, a monk picks a ripe little tea leaf. The evocation of attention together with the conveyed sense of space make sound integral in establishing the dimensionality of a cinematic image and its contemplative quality. We tend to look at an image and, once recognizing what it is, move swiftly on. The thought is there, “oh, the monk is gardening” and then immediately there is that compulsion, wanting to know what happens next. I like a film that stays put and allows for attentive looking and listening. Within the frame, the eye can scan, exploring the details of the image. Not unlike the sustained gaze of observation we cultivate in our meditation practice.

The Inner Landscape

“If we opened people up, we’d find landscapes. If we opened me up, we’d find beaches.”

(Agnès Varda 2008)

The traditional narratives alive at Zhenru connect those who live and practice there to more than just a culture—they speak to real, embodied inner experience, as with the story of Sudhana’s journey. Over the centuries, these are the narratives that survived cultural “natural-selection” to be recounted by Zen masters and rendered by Zen artists as powerful tools to inspire, guide, and communicate inward contemplative experience.

What we experience in meditation is of a realm beyond the reach of language. So how to express the ineffable? Perhaps through experience itself. Experience requires no language. It is lived, in our body and in the primordial mind. And so in the master-disciple dialogue things which are experienced often stand in for language. Just as hearing descriptions of love cannot move one to fall in love, explanation of stages of concentration cannot concentrate your mind. But you have tended to the family oxen. You’ve chased them across fields and into dense woods. You’ve hoed the fields, felt the weight of the soil and smelled the raw earth. That lives in you as a visceral, tangible experience. So the master or the artist evokes this kind of experience as something that shares the quality of a meditation experience. It cannot invoke a state of mind which has not been earned through practice. But it can serve as a signpost along the way, to guide us. As one hermit master in , The Mountain Path (2021) says,

“Wherever your mind is, the scripture speaks of it and you feel you’ve arrived… the scripture may speak of something but your heart’s not there yet. So you must go off and practice some more.”

As the traditional Zen narratives around me at Zhenru began to relate to my contemplative practice, I naturally began to wonder how I might employ the elements and qualities of cinema to speak to these narratives as a guidepost to understanding the ineffable?

To begin, I think it is important to establish a structure and a grammar that allows for images to belong simultaneously to both our inner and outer realms of experience. This is not new to cinema, and many great filmmakers work in the realm of dreams, memory or ecstatic vision. So we can start from there to establish the cinema frame in that gaze, capable of looking upon the unified field of experience that the contemplative traverses. Tarkovsky, Ozu, Herzog, Malick, Varda, and Lynch guide me.

I agree with Andrey Tarkovsky when he says that working within the inner realms is working with life at its most true and so, the images should look true.

I would say that in cinema ‘opacity’ and ‘ineffability’ do not mean an indistinct picture, but the particular impression created by the logic of the dream: unusual and unexpected combinations of, and conflicts between, entirely real elements (Tarkovsky 1986, p. 72).

How we invite the audience to accept an image as dreamscape is in mise en scène, and the “logic” of the edit. And so it is with contemplative cinema, to edit in the logic of the contemplative gaze. There are certain edits — cued by rhythm of edit or sound, dialogue, or a character’s gesture — that are pregnant and powerful shifts in vision, toward the inner-landscape view. Like in a traditional POV shot. But the image belongs to the inward gaze — surveying the mindscape — or to the unified field of experience where the contemplative abides. I think Herzog and his editor Joe Bini have mastered this approach in Encounters at the End of the World (2007).

In THE MOUNTAIN PATH, I have cut in many such moments; the hermit nun gazes out her doorway, as if it were a portal to her own life, collecting wild plants on the forested mountainside. Also when we cut from a long shot of a dynamic cloud-capped mountain to a moment where my teacher is looking off, gazing inward in memory. These are just a couple examples.

If a film succeeds in making the audience familiar and comfortable with this shifting between realms of vision, then the contemplative gaze finds its full fruition when we can no longer say for certain if what we are seeing in the frame of the cinema screen is the character’s gaze upon their world, or upon themselves—their inward gaze. Tarkovsky’s Nostalgia plays in this reality. Taking us seamlessly between dream and waking. Now we are working with both what the character sees and how the character sees, simultaneously. We are in the contemplative gaze.

Looking out at mountain landscapes, or a great sprawl of farmland or a bamboo forest, these landscapes are nothing other than the character’s own inner landscapes. Now the film can play in that space, with all elements of landscape available—like a drop of rain or a drifting cloud, an insect or an ox, swift and fleeting birds.

In ONE MIND, in keeping with the very structural “fortress” element of the Sudhana story, I looked for ways to establish a strong sense of this spatial grammar in the film by using images with a strong feeling of spatial definition—features of architecture and natural landscape. I began by thinking, for example, of the monastery—and by extension, the inner-sanctum of the meditation hall—as Maitreya’s fortress. There is no need for precision here. We are working in atmosphere, not metaphor. In both ONE MIND and THE MOUNTAIN PATH, this physical sense of formality, married with moments of gazing, maybe closing or closed eyes, images and sounds of doorways, and the impression of moving into and out from spaces sets the groundwork for these shifts in point of view from the internal to the external and back again.

Who Is Looking?

When I consider how to compose an image, I think of how it will live in the frame of the cinema screen. That box of light on the wall is a portal into a full world the filmmaker creates. Beyond the frame extends an entire reality; there is space there, and time too. When we approach cinema in the contemplative gaze, and we are working with the structural, formal voice of the film, the cinema-space comes alive in its original, true power. It brings to the fore something innate and primal to cinema itself, and because this cinema-space shares so much in qualities with mind itself, these cinema images evoke a very mysterious effect in the viewer. A kind of resonance occurs between the cinema-space and the inner landscape of the viewer. It opens us up to that sense of space within us, and we feel grounded in that sense of being awake inside. I think this is Dorsky’s “alchemy”—the union of materiality and subject matter he so eloquently describes in Devotional Cinema (Dorsky 2014, p. 25) A cinema that speaks to and connects with the viewer on the level of mind itself. Cinema that resonates with the forms and mechanisms of mind, as in meditation. Not with mind’s fleeting mental objects.

Within this cinematic formality, established by visual and audial shaping, the frame—and I mean the cinema screen itself—is energized, empowered as a reference point. Establishing a point-of-view. The question who is looking? emerges. Something distinctive to Zen contemplative inquiry. Even in the completely still frame of Ozu’s films, for example, there is a sense of looking. What most filmmakers would capture with camera movement, Ozu somehow manages with disciplined stillness. I think it is a misunderstanding to say that his cinema gaze is an enlightened gaze. In fact it is the gaze of someone toiling along on the contemplative path.

In the case of ONE MIND, establishing this grounding in form, and not presenting a character arc to follow, is intended to shift the perspective of the film away from a reactive posture and away from emotional absorption and distraction. This is not meant to leave you suspended in a void, but to settle you into the gaze itself. The viewer is free to respond to the film’s subject—as nature intends we do—but grounded in the contemplative gaze. We experience ourselves in that scene.

More often than not, films ignore this formal quality of the cinema-space and use it simply as a void to fill with story. It can even sometimes be imbued with an aggressive point of view, calling us to respond emotionally, dramatically, and get carried away in the plot, wandering in a web of impulses. But here we are crafting cinema in the image of Buddhist contemplative values, so we engage this quality of film to find our footing and ground ourselves in the mindscape within us like a watchtower from whence we can relate to our unfolding life with illumination and an intention toward healing insight.

The larger structure of ONE MIND is meant to enforce this gaze. My partner and co-writer of ONE MIND, Agnes Lam and I were very deliberate about the grammar of the opening text and chapter text. Maitreya is talking to you. You are the “Young Pilgrim”:

Young pilgrim,

Do not turn away from

the unruly ox that runs wild

in the forest of your mind. (ONE MIND 2015)

Throughout the film, too, are nods to this grammar. There are images where the inner landscape of the frame is meant to be for you. Especially the ox. This is a deliberate shift in the grammatical structure.

Some people tell me the quiet scenes of domestic monastic life ease them into a calm and easy rhythm. Others feel ill-at-ease listening to the sound of the razor scraping over the monk’s freshly-shaved head. I feel in both cases I got something right.

People sometimes say ONE MIND does not have a plot. But I like to think it does. It is just that the plot is not happening inside of the film, it is happening inside you. In ONE MIND, you are the Pilgrim Sudhana. The scenes you are gazing upon are the inner landscapes of a very special, deliberate spiritual community of meditators living in the mountains of Jiangxi Province. But the journey is all yours.

I want ONE MIND to connect the viewer to the challenges of deep contemplative practice—that an authentic contemplative life—like we see at Zhenru—is not all peace and bliss. We are Buddhists, not buddhas! These men are struggling the same as we struggle. And while I think we owe them a great respect as people who have chosen to take this struggle on with the entirety of their being and the whole of their precious lifetime, they want us to also plant our feet and stay put and look life in the eye as they do. I hope that ONE MIND, as a viewing experience, invites each viewer into this very whole and authentic posture toward life. As I went searching for it many years ago.

Conclusions

At Zhenru, I discovered a commitment to contemplative life on a community level, where all things reflect basic contemplative values of insight and illumination. As a whole, this kind of monastery is a microcosm for what community can look like when we choose to take on that shift in perspective together and craft our environment in the image of those values, to tell those stories to one another and move toward that vision together. Capturing that in film meant I had to look not only at what these monks live but how they live. And cinema was a perfect vehicle for that because with cinema, I could show you the place and the people as they appear in the contemplative gaze. Cinema can move between the inner and outer realms seamlessly and without hindrance, just as our minds can and do.

The contemplative life is about living life as we live in meditation. Showing up, and staying put. Grounded, not distracted. Inquiring, not averse. Illuminating, not reactive. So, I see contemplative Buddhist art, and cinema included, as a profound kind of public protest against our own confusion. And by extension, against the status quo of suffering and abuse in our world born of that collective confusion. It is a radical thing to turn one’s gaze within.

All stories are worth being told, joyful or painful, gentle or violent. But there is a toxic way to tell a story and a healthy way—with an open-heartedness and an intention toward reconciliation with darkness and joyfulness. And I think this is the greatest gift that art can give us. It empowers us to relate to ourselves in a more authentic way and when we can do that naturally, we begin to heal, and when we heal, we evolve.

Years ago, at a monastery in the north of China, a close teacher of mine said to me: A buddha is a being, like you or I, who has awoken from the dream of ignorance. That makes us all dreaming buddhas. Much is written about how to tackle dreams in cinema. But how to tackle the dream? We can approach cinema with the same techniques as master filmmakers like Tarkovsky or Herzog. We can carry the audience along on a trip into the inner landscapes. And that is really great cinema, but it is not Buddhist contemplative cinema. What makes cinema Buddhist is in the recognition of the big dream and the aspiration to wake up. Once we make this vow, we step into a life with new intentions. The contemplative gaze is about working toward wholeness and unity of mind - the foundation for kindness. And that is why all of this matters—art, cinema, meditation. Art is not all about creating things, it is also about learning to see with an artful gaze. Learning to look.

References

(Amongst White Clouds 2005) Amongst White Clouds. 2005. Directed by Edward A. Burger. Calgary: Cosmos Pictures.

(Cho 2017) Cho, Francisca. 2017. Seeing Like the Buddha. Albany: State University Press.

(Dorsky 2014) Dorsky, Nathaniel. 2014. Devotional Cinema. Berkeley: Tuumba Press.

(Encounters at the End of the World 2007) Encounters at the End of the World. 2007. Directed by Werner Herzog. Silver Spring: Discovery Films.

(Kerouac 1958) Kerouac, Jack. 1958. The Dharma Bums. New York: Viking Press.

(ONE MIND 2015) ONE MIND. 2015. Directed by identifying-text-removed. Wooster: Commonfolk Films, LLC.

(Porter 1993) Porter, Bill. 1993. Road to Heaven. Berkeley: Counterpoint Press.

(Red Pine 2001) Red Pine. 2001. The Diamond Sutra. Washington: Counterpoint.

(Schrader 2018) Schrader, Paul. 2018. Transcendental Style in Film. Oakland: University of California Press.

(Tarkovsky 1986) Tarkovsky, Andrey. 1986. Sculpting in Time. Translated by Kitty Hunter-Blair. Austin: University of Texas Press.

(Tarkovsky 1983) Nostalghia. 1983. Directed by Andrei Tarkovsky. Italy, Soviet Union: Rai 2, Sovinfilm.

(Trungpa 2008) Trungpa, Chögyam. 2008. True Perception. Edited by Judith L. Lief. Boulder: Shambhala Publications, Inc.

(Varda, Agnès 2008) The Beaches of Agnès. 2008. Directed by Agnès Varda. France: Ciné-Tamaris, ARTE France Cinema.